Remembering the Student-G.I. Anti-War Movement

When I came home from Europe in September 1968, the antiwar movement was not new but it was gaining momentum. Young guys my age faced the threat of induction. I was called up twice for the pre-induction physical, but I managed to stall the first draft order by extending my student deferment and the second by submitting a conscientious objector claim on humanitarian grounds. This confused my draft board just enough so that my newly assigned lottery number put me barely over the line. When I was safe at last, a stomach ulcer I had been suffering for years magically disappeared. I entered a state of serene joy.

Back in 1968, most males my age were in the same boat. Draftees were dying in the jungles of Vietnam, as many as hundreds a month. Land mines were sending home guys like me without their lower limbs. It was also a time of personal liberation and flowering youth culture. Hardly anyone was eager for a brutal basic training with its shaved heads and screaming insults followed by on-the-job training in murderous jungle combat. The opposition to war and military discipline was spreading, not only from the students to the general population; it was making inroads in the military itself. Instead of today’s smarmy “Thank-you-for-your-service”-hypocrisy, antiwar activists inside and outside the military insisted that “supporting our troops” meant working against the system that forced them into uniform and sent them off to death and destruction in an unjust and unnecessary war. Everyone knew that moneyed interests profited from the war while poor and Black draftees stood to lose everything. It was equally obvious to anyone who knew history—and we became avid students of history—that Southeast Asia was only the latest front in a long and many-faceted anti-imperialist struggle. Despite the fog of lies that later distorted the antiwar movement (the legendary returning soldier who is scorned and spat upon, like Jesus, by vile protesters), we knew that we were acting in support of the countless resisting G.I.s and against war and imperialism. Two friends from my first year of college had been drafted and sent to Vietnam. One stepped on a land mine and came home in a coffin. Everyone knew someone.

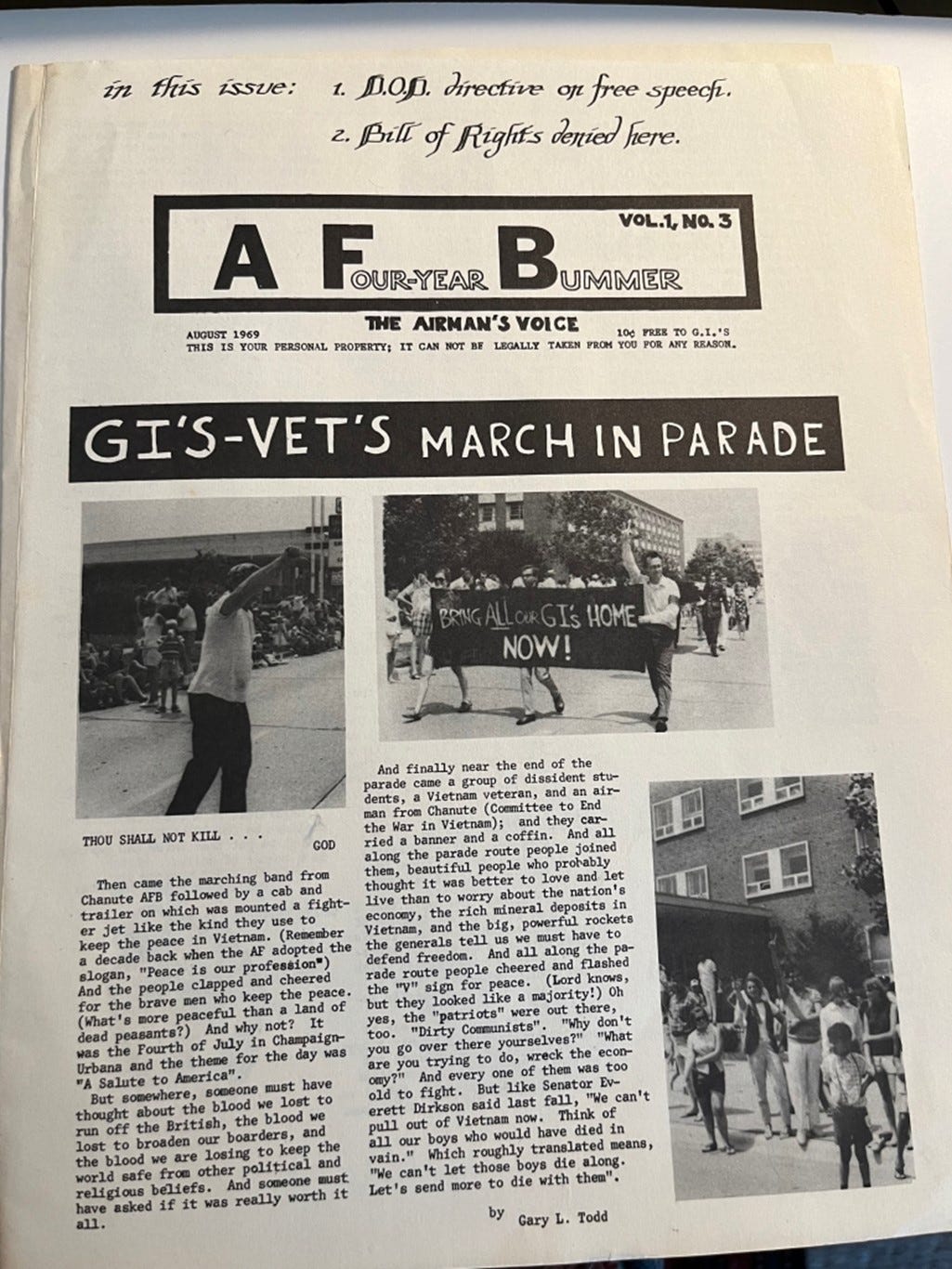

In early 1969, I teamed up with an independent radical student to publish and distribute an antiwar paper for airmen at the nearby Air Force training base in Rantoul, Illinois. The project had been initiated by the Trotskyists of the Socialist Workers Party, but the main local organizer was moving away and leaving the paper in the capable hands of Gregg Gauger, a student my age. Gregg and I hit it off immediately; and soon a collective of students and independent activists coalesced around our efforts. We were surprised by our success. The first time I handed out papers at the gate of the military base, my collaborators and I were accosted and threatened with violence. We suspected that this was at the instigation of the base officers. Soon, however, we were being thanked and congratulated by the airmen. Unlike the army, the Air Force recruited only volunteers for four-year terms of enlistment—a long time when you’re young. Contact with students brought a whiff of free association. At the G.I.s’ suggestion, our antiwar paper was called “A Four-Year Bummer,” a play on A.F.B. (Air Force Base). This summed up the feelings of these young men trapped in the military while their equals in age were partaking of all the exhilarating activities of the time. Within two years, the communal house rented by our collective in Urbana was filling up on Saturday evenings with dozens of bored and disaffected servicemen. We offered free legal counseling and an open-minded atmosphere for those who were sick of military life. Some had only volunteered for the Air Force to avoid being drafted into the army. Some already knew enough about the conduct of the war to be against it. My older brother had flown reconnaissance missions over the Gulf of Tonkin in 1966-67. He was against the war after seeing how aircraft-carrier-based pilots dropped their bombs indiscriminately in order to be eligible for awards and promotions.

Our collective, of which Gregg was a co-founder and I was next in seniority, had a place for everyone: gay and straight, Black militant and white liberal, radical and moderate, Christian-pacifist and hard-core Leninist, Trotskyists of more than one stripe, Hippie anarchists, and Communist sympathizers. We were open to any oppositional voice, though Gregg and I exercised veto power over content. Anything that promoted our antiwar and pro-G.I. purpose was accepted. Anything racist, sexist, classist, or homophobic would have been rejected. But I don’t remember that this was ever a problem, since we were united by a common cause and by the same basic truths. We were not an “intersection” of “identities” jockeying for recognition of particular grievances. I was probably the oddball, since I was continuing my philosophical, philological, and literary studies. I remember the good-natured mirth my textbooks for the old Gothic language provoked among my comrades. Many of us considered our academic studies irrelevant. The coming revolution would change everything anyway.

Much of our work was the routine effort of producing and distributing our publication and meeting with servicemen. Like most leftist groups, we kept a mailing list of other movement publications with which we exchanged gratis copies. Everyone was free to take whatever was useful of ours with or without giving us credit. We didn’t sign our articles (a token of bourgeois private property!). I remember once finding my analysis of Vietnam as a capitalist and imperialist war reappearing as the centerfold of the Black Panther Party paper. Since mailing lists got passed around, we sometimes received unexpected “presents” such as the beautifully bound complete edition of North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung’s “works.” They might have ended up on the shelves of some rich philistine too indifferent to the content of these leather-bound adornments to care what was inside.

There were two memorable semi-violent incidents: one marked a high point in our effectiveness and the other its bitter end. On the 4th of July, the Left always marched in the patriotic parade with our antiwar contingent which came to include a handful of antiwar airmen. This was allowed as free expression, but only as long as the demonstration didn’t involve any sort of violence. In 1971, the parade organizers tried to entrap us with the help of the police. We were told by the organizers that we would go first. Just west of the corner of Lincoln Avenue on Green Street, police cars blocked us from behind when the parade stalled in front. On cue, angry local men rushed out and tried to seize and destroy our signs and banners. Our people had enough muscle to fight back and hold our ground. The problem was that the servicemen in uniform could no longer participate. Our people fought until the parade moved on with a few of the sulking heavies straggling along with us. Meanwhile, I led the airmen with signs and banner via short cuts and back streets. We arrived before the parade and occupied a space between its route and the reviewing stand. We were right under the nose in the line of sight of General Knapp, the invited AFB commander. The incident made for an edition of the paper that was eagerly received and read at the base gates. The whole thing was fun, and it convinced airmen that they had little to fear. Later there were disturbances on the base, instances of an Armed Forces insurrection that historians see as a significant factor in stopping the war, ending the draft, and pressuring the government to transition to a volunteer army. We could claim that we did that. We certainly contributed to it. But I’m not sure now what our agency amounted to. We were like a surfer riding a cresting wave who gets a spurious sense of controlling the flow. Our success resulted from our joining, not leading, the movement. At best, we can claim that we understood the situation and seized the right moment.

The other semi-violent episode in late fall 1971 put an end to our collective. It was really a manifestation of what could be called the Surrealist Left. It was a bleak Saturday night in November. I was recovering from a nasty stomach ailment, on the mend but still weak and keeping my distance. Coming back to our house with my clean clothes from the laundromat, stepping inside among a full crowd of servicemen, I was startled by the angry voice of a Black ex-convict from the North End of Champaign. Standing in the middle of the room alongside an older local radical and four members of our collective, this self-styled Black Militant and Panther wannabe was screaming in the obscene and threatening style of the time about certain traitorous motherfuckers in our midst. Two things soon became apparent: first, that the group in the middle of the room was not interested in discussion. They were there to call out traitors. Second, the right hand clutching a bulky pointed object in the right pocket of their matching black jackets was meant to imply a loaded handgun. The servicemen quietly emptied out of the house. The rest of us had to listen to several hours of drug-fueled haranguing before they were running on empty, setting off for whatever it was they craved on the downside of their trip.

Two things explained this strange scene. A few weeks earlier, we had invited Andy Stapp of the American Servicemen’s Union to give a talk. Stapp and his comrade John Lewis were older veterans of the struggle who belonged to the Marcyite, ultra-leftist Workers World Party. The WWP was descended from the splintering American section of the Trotskyist Fourth International. They had split from the more timid SWP over, among other things, the suppression of the Hungarian uprising of 1956. The ultra-leftist WWP supported the suppression of its “counterrevolutionaries” by East Bloc tanks. Since then, they had been positioning themselves as the vanguard of the most militant movements and tendencies. When the SDS successors declared their Days of Rage smashing windows on Michigan Avenue in revenge for Mayor Daley’s brutal crackdown on demonstrators at the Chicago convention, only the militants of the WWP joined in the pointless and doomed offensive. The WWP tried to ally themselves with, and co-opt, the most militant elements of the Sixties, whether armed Black Liberation or the Weatherman faction of the SDS. They had sized up our group as ripe for splitting and taking over. They had cultivated a faction of our collective as their instrument. And they had concluded that the main obstacle was, not Gregg or me, who might still be useful, but rather several members of our collective who they suspected were secret adherents of the arch enemy of all Trotskyists: The Communist Party. Those members had borne the brunt of the drug-addled invective of our captors on that November night. And lo and behold, their intelligence sources had gotten it right: the targets soon came out as Communist Party members. For decades, they would serve as the core cadre of the CP in Illinois.

But the Marcyite WWP didn’t disappear either. With an obstinacy found in my experience elsewhere only in the German Left, they continued on the same path. My friend and comrade Pancake was initially and for a time beguiled by them.

Gregg and I rented an apartment on the far side of town and went back to our studies. I carried on as an ad hoc activist; but it was never the same again; and after completing my studies, I lived in places where I was cut off from what had once been “the movement.” My high activism was an episode of about four years in total, though when you’re young, four years feels like half a lifetime. Living abroad in Europe or isolated in the Green Mountains of Vermont, or south of Bloomington, Indiana, or in Southern Illinois, I was more like a Rip Van Winkle of the Left, abiding in its moment of success, than one of the renegades. My brief period of activism saved me from the cynicism of decline and the apolitical funk of so many who never really knew what they wanted. My experience gave me a sense that the individual can radically change and, in comradeship with others, alter the course and history. It’s a matter of seizing the right moment and of banding together with others who share a clear understanding of the reality of the situation and the objectives of the struggle.